IT'S ABOUT TIME!

Time, she's a fast moving train. She's here and she's gone and she won't come again.

If that is the case, focusing on politics or TikTok videos is probably not a great use of it. Planning for the future might be better. We are often reminded that the earlier we start saving the more we can benefit from the magic of compounding and the longer we put off saving for retirement the sums necessary to meet our goals become staggering. Time can be our friend - or our enemy.

The problem was that post-war-Germany was as destitute as the victors. It had consumed its wealth in manufacturing war materials, it too had suffered terrible loss of life and its cities were also in ruins. The victors insisted on being paid in gold knowing that it was too easy for Germany to simply print worthless paper marks. As Germany was forced to make reparations payments in gold-backed marks, this left German citizens with little currency to pay for essentials such as food and shelter. Consequently, the government printed and distributed unbacked marks to support the basic functioning of its society.

That worked for a time but there was always a shortage of physical currency. So more was printed. As it circulated prices began to rise - slowly at first and then more rapidly. This led to demands by workers for higher wages to pay for the increasing prices of goods and services. More currency was printed and distributed in ever increasing quantities with the result that each new mark was of far less value than those formerly in circulation. Due to labor strife and factory closures German civil society began to break down. Farmers refused to deliver food to the cities because the devalued money they were paid did not begin to cover their costs of production.

Throughout this episode, no one understood that the problem was not higher prices. High prices were the consequence of something else. And that something else was the vast expansion of the money supply. They failed to appreciate that expanding the money supply does not cause goods to spring into existence. The first step necessary to end rising prices was to cease printing more money. The second step was to tie the mark to something of real value to encourage Germans to hold onto marks rather immediately spend them to protect their falling purchasing power. Many stop-gap measures were tried and failed (new currencies that were also printed in vast quantities). Confidence was achieved only after years of human misery. As a result, Germans are to this day notoriously conservative about their money and are opposed to their central bank (now the ECB) giving into political demands to print money to "solve" an endless litany of social and economic issues.

The reason is that politicians always reach for the easy answer even when that answer is obviously flawed. For example, President Biden raided the nation's strategic oil reserves in an effort to lower gasoline prices before the mid-term elections. That reserve is now at a forty-year low. It was not created to be a piggy bank for politicians but it has been used for that purpose. The price per barrel that will have to be paid to replenish the reserve will likely be very high. Biden's solution? Make nice with the dictators of Iran, Venezuela and Saudi Arabia so that more oil will be produced to lower the price. His plan includes frustrating the importation of Canadian oil (from a nearby, friendly and reliable democratic regime) and hampering the production of domestic US oil. Thus, the US will become ever more dependent for essential energy sources from autocrats who routinely express their deep animus toward Americans. Most people have no difficulty understanding that Germany's dependence on Russian gas was a monumental strategic error, yet they are oddly oblivious to the comparable danger of Biden's plan.

Central Banks - From A Good Concept To A Disaster In Practice

Investors have come to believe that central banks exist to support the investment markets and should come to their rescue whenever they face setbacks. They are further encouraged to believe that central bankers have the knowledge and expertise to act as ring masters for their nation's economy. In order to dispel these myths it is useful to review why central banks were created and what they have morphed into over time.

All banks are illiquid. They take in short-term deposits (savings and checking deposits) which can be called away on a moment's notice and give out long-term loans (30 year home mortgages, 5 and ten year business loans). They keep some cash on hand to cover expected withdrawal demands. Occasionally, they are met with unexpected withdrawal demands. The movie "It's a Wonderful Life" portrays such a crisis. During these "runs" banks were often forced to close and default on their depositor obligations. FDIC insurance was created in the US to protect depositors and discourage sudden demands for cash by nervous account owners.

The US Federal Reserve Bank was created to provide temporary liquidity to banks during stressful times. However, the rules were clear. The Fed could only provide money to a distressed bank in an amount equal to its "sound" loans - and then only at a "penalty" rate of interest to discourage frivolous use of the system. Such Fed-supplied loans allowed the threatened bank to meet the unexpected circumstance and live to fight another day. If the bank did not have sufficient sound loans on its books, it was to be closed and its assets sold off. One can argue whether this scheme created "moral hazard" (an incentive for banks to take ever-larger risks knowing they will be bailed out if things go wrong) but the system worked reasonably well for a long time.

The problem started when the Fed decided that it wanted to play a far larger role in the economy than being "lender of last resort" to solvent banks. There is always relentless political pressure on the Fed, from whichever party is in office, to make cheap money available to "stimulate" the economy in order to benefit current office holders. The Fed should be deaf to these calls. The problem is that Fed officials are political appointees and therefore are highly subject to political pressures.

Elected officials tend to get thrown out of office when the economy suffers so they endlessly badger the Fed to take actions that may have short term benefits for the politicians but long-term detriments for the economy. The Fed should never allow itself to be used to advantage political careers but they do so regularly. This creates an obvious problem: how is the Fed to know whether the economy really needs stimulating, in what amount and for how long? It makes these decisions by relying on its 400+ Ph.D economists who create complex mathematical "models" of the economy that they believe will reveal just the right action to take, at just the right time and in just the right amount.

As we have recounted many times, the Fed's models have proven to be grossly flawed. They have repeatedly failed to anticipate monetary problems and then allowed monetary interventions to continue for far too long. This creates new problems flowing from their "solutions" to the last problem. Fed officials are routinely wrong about the state of the economy. Alan Greenspan refused to admit that the stock market was in a precarious bubble in 2000. Disaster followed. Ben Bernanke insisted that there was no bubble in the real estate market and that the towering property prices in 2007 were fully justified. A short time later, major US banks were brought to their knees as the real estate market collapsed. The Fed's go-to "solution" was to bail out the banks that had foolishly brought about the bubble by printing and distributing trillions of dollars to them that then generated new asset bubbles that later deflated creating new crises.

The Fed has proved time and again that it has no powers of prediction concerning the state of the economy or the consequences of its actions. Chairman Powell assured us in 2021 that, based on Fed monetary models, price inflation of just over 2% was "transitory" and no action was required of the Fed to stem it. He was egregiously wrong. History proves that the Fed is not competent to manage the vast US economy much less supervise the major Wall Street banks (its real job, that it neglects). It should be returned to its limited role of lender-of-last-resort to solvent banks. The US economy is far too big and far too complicated to be micromanaged by a handful of bureaucrats in Washington DC - few of whom have actual business experience in the real economy. There is collective political and economic amnesia about the USSR's centrally-planned economy debacle. Yet, the public still looks to the Fed to solve the current inflation problem - that it created.

The US Economy

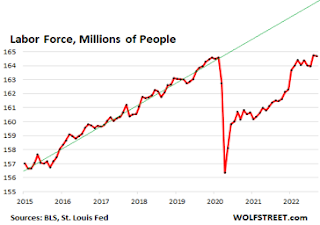

Despite everything Americans are told by the media and their political leaders, there is very little about the US economy to cheer. The labor force is still far below trend.

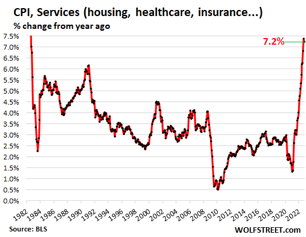

Price inflation for "services" remains very elevated and will continue to pressure prices higher.

There is nothing remotely “sound” about Britain’s welfare bill being set to rise by almost £90 billion, funded by a stealth raid on wages and higher levies on business.Nor is it “sound” to be pumping an extra £6.6 billion into the NHS over the next two years without any reform whatsoever. What is sound about recruiting more doctors and nurses and rebuilding hospitals when patients still can’t get a GP appointment or an ambulance and have to wait months for an operation? This country is fast resembling a health service with a government loosely attached.

Just about everything in Britain these days seems to be in decline or otherwise going to hell in a handcart. Increasingly paralyzed by strike action, idleness, and bureaucratic obstruction, the UK economy is once more slipping into the sea, just as it was in the 1970s, with hopelessly poor levels of productivity, plunging relative living standards, and crumbling infrastructure.It almost beggars belief that the profound loss of international competitiveness that defined that troubled decade should now be repeating itself. It's going to require similar shock therapy to once more pull things back from the brink.Yet there is little sign of the political appetite, let alone will, for it, or indeed wider recognition of quite how parlous the UK's position truly is. It is not as if the UK is objectively any more insolvent as a nation than much of the rest of Europe, or even the US, where if anything public debt metrics look even more troubling.But there is a crucial difference; Europe is underwritten by hair-shirted Germany and its northern satellites, while the US has the world's dominant reserve currency, and can therefore borrow with impunity almost however bad the public finances look. The UK by contrast is on its own. It also has massive household debt and a yawning current account deficit to maintain. Ever since Brexit, international investors have had a deepening downer on the UK. Britain is in a downward spiral from which there appears little prospect of escape. Almost unbelievably, nearly a quarter of our working age population is reported to have some form of long-term illness or disability.

Japan, with an aging and shrinking population, continues to rely on money printing and repressed interest rates to keep its economy spinning. "I believe we won't be introducing a rate hike anytime soon," Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda told a news conference. "We have decided to continue the monetary easing after thoroughly discussing what the most effective monetary policy is by analyzing the Japanese economy, price trends and future development in depth." While Japan has largely avoided the pain of high inflation that is being suffered in the West, it cannot do so forever. Its shrinking population is most noticeable in the youngest ages (0-14 at the bottom, below) and working ages (15-64 in the middle). Fewer workers leads to shrinking GDP and less ability to support the elderly and the government.

For those who invested in the Nikkei stock index, the suffering continues. It hit a high of 40,000 in 1990. It has never recovered. It is currently around 28,000. That is a thirty-two year lesson in the damage inflicted on the nation by its central bank-induced real estate bubble.

China still struggles with Covid because Xi Jinping has maintained a "zero Covid" policy even though that is imprisoning whole cities and adversely affecting Chinese GDP. Xi continues to consolidate political power and replace high officials with his sycophants. His adamant position that industry be subservient to the state may help him to consolidate power in the near term but it will eventually retard China's industrial progress. The biggest international concern is his insistence that China will dominate and control Taiwan. That is a far more serious issue than Putin's war in Ukraine. It threatens world calamity.

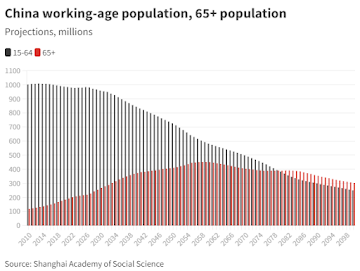

The shrinking of the Chinese working age population compared to the 65+ population is a huge problem over which he has no control. This growing catastrophe directly flowed from the government's ill-conceived "one-child" policy. The chart below shows the rapidly shrinking working-age population (black lines) compared to the 65+ population (red). Absent stupendous productivity growth, this is will lead to a financial and social disaster.

Xi Jinping’s China is in an economic trap with no easy way out. Debt saturation has passed the point of diminishing returns – indeed, classic debt deflation has already set in – and the growth model built on construction and heavy industry is beyond exhaustion.

“They know they can’t keep putting their foot on the credit accelerator and wasting money on useless infrastructure,” said George Magnus from Oxford University’s China Centre.Youth unemployment has doubled to 20pc over the last four years and this is a red flag for the Communist Party, still haunted by the student defiance of Tiananmen Square in 1989.Political stability depends on finding a way to draw 11 million graduates each year away from the hothouses of Weibo and Wechat, and safely into the Leninist bourgeoisie. The path of least resistance is to export China’s unemployment to the rest of the world with a beggar-thy-neighbour trade strategy, boosting exports through a stealth devaluation of the renminbi or through (further) covert subsidies.

Western nations will strongly resist this effort as it imperils their own economies. The best we can hope for is that China's many internal problems will demand Xi's full attention so that he does not press for the reunification of Taiwan any time soon.

Important Message: The foregoing is not a recommendation to purchase or sell any security or asset, or to employ any particular investment strategy. Only you, in consultation with your trusted investment advisor, can select the strategy that meets your unique circumstances, investment objectives and risk tolerance. © All rights reserved 2022

.png)